I’m in a book club. Yeah I know—typical suburban mom thing. But I find it’s not only a good excuse to hang out with girlfriends but also to read books I never would have picked out on my own. Occasionally, a book gives me new insight into a topic related to my work.

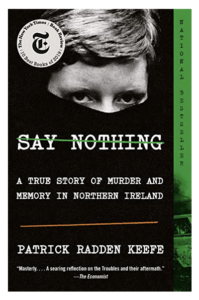

One such example is the book Say Nothing, an excellent work of “narrative nonfiction” (totally factual material presented in a novel-like story) about Irish Republican Army fighters during the Troubles of Northern Ireland. This book helped me better understand a disturbing but common phenomenon:  how insurgents end up doing so much violence to the very community they’re fighting for.

how insurgents end up doing so much violence to the very community they’re fighting for.

Here’s how it happens. When a government (or occupying power, for that matter) is facing an insurgency, its military seeks to capture or kill insurgents. But those fighters, by definition, are not marching around in neat formations wearing uniforms. Instead, they melt into the population. The military has to answer a simple question: Who are the insurgents? To answer this, they have to rely on human intelligence. And so they pay ordinary civilians to get them to reveal who the fighters are. In any armed conflict, the economy is a wreck, so it’s not hard to find desperate people willing to give up information in order to feed their families.

Now look at it from the point of view of insurgent leaders. The government forces are targeting them, and to the extent they’re doing so accurately, it’s because of those informants. So they have to discourage civilians from becoming informants and put an end to the ones who are informants already. This is critical to their self-defense. And if you’re in an insurgency, there’s probably no way you can set up police, courts, prisons… so “justice” is brutal and swift. This can mean interrogating, torturing, punishing (through serious violence, like “kneecapping” in Northern Ireland), and/or killing the suspected collaborators.

The atmosphere becomes one of intense distrust as everyone on both sides tries to figure out who the informants are. This is not irrational, because the existence of informants is real. Needless to say, though, they often punish the wrong people. I once talked with an elderly man who was a prominent figure in the African National Congress. He described with sadness the killing by the ANC of a young woman who was suspected of collaborating with the Apartheid regime. It came out years later that she was innocent of the charge. He expressed deep regret about that—but he did not regret the practice generally, only the case of mistaken identity.

Before you know it, the insurgents have harmed or killed hundreds of their own, and the population lives in constant fear. The armed groups seeking to liberate and benefit their community have instead brought more violence and injustice to them. They didn’t set out to do this when they first took up arms, but they’re caught up in the demands of the moment. Meanwhile, the government or occupying power points to the phenomenon as evidence of moral depravity and the unfitness of the self-described liberators to govern. All of this is one way a conflict takes on a life of its own and becomes difficult to get out of without third-party help.

I’ve never seen any research on this dynamic of violence against suspected collaborators or any practical ideas around how to limit it (please tell me if you know of any), but maybe we should start brainstorming. Meanwhile, would-be insurgents should think about this phenomenon carefully before turning from nonviolent to violent resistance, and peacemakers should take the terrorizing of civilians into account and keep the unarmed population’s needs front and center in any peace process.

Can I join this awesome book club? 🙂 I really appreciate the nuance with which you relate insurgent violence, and three book’s premise. Sounds like a great way to lose hearts and minds rather than win adherents.

Thanks Anthony. Come on out to CO and you can be our book club’s token man 😉