Where you were on September 11, 2001? (I bet you remember the day as vividly as I do.) I slept late that morning, having been up on and off all night with my then-six-week-old baby. The first weird thing I encountered was a voice mail from my father assuring me that my brother, who worked in Washington, DC, was OK, though he’d begun a long walk home from the office (?!?). Then my husband called from work and said, “Do you know what just happened?!” and proceeded to describe the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. I was in a daze, but I turned on the TV and saw the images that we’ve all seen hundreds of times since. It was surreal — it seemed like a movie. It took me some time to absorb that this had really happened and to feel all those things one feels after a terrorist attack: shock, pain, sadness, anger, rage, fear, helplessness, hopelessness. We feel them all over again, especially when another attack happens in the US, or in Europe — the kinds of places many of us might visit on business or vacation.

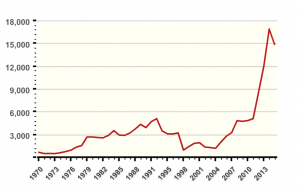

It’s not your imagination: terrorism is up in recent years. Check out this graph  from the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) — it shows the number of terrorist incidents worldwide 1970-2015. Notice, in particular, the dramatic rise from 2004 to 2014 (and let’s hope the decrease of 2014-2015 continues).

from the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) — it shows the number of terrorist incidents worldwide 1970-2015. Notice, in particular, the dramatic rise from 2004 to 2014 (and let’s hope the decrease of 2014-2015 continues).

Now for what might be a surprise. Even with this steep increase, terrorism is not replacing war as the major form of political violence: In 2015, about 80% of fatalities from organized violence were in “state-based conflicts” meaning where at least one party to the conflict was a national government (see Melander, Petterson & Themner 2016, “Organized Violence 1989-2015,” Journal of Peace Research and this graph) — so basically war.

And terrorism is most certainly not concentrated in places like France, Belgium, the UK or the US. In 2015, “More than 55% of all [terrorist] attacks took place in five countries (Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, and Nigeria), and 74% of all deaths due to terrorist attacks took place in five countries (Iraq, Afghanistan, Nigeria, Syria, and Pakistan)” according to the State Department and START. Notice those lists of countries. What do they have in common? While some have raging civil wars, ALL of them have internal armed conflict between one or more rebel groups and the state, producing at least 25 battle-related deaths per year.

So let’s put this together: Terrorism is up, but most most deaths from organized violence come from bad, old-fashioned war (or the lower-intensity versions thereof). And most terrorism comes from the very countries experiencing that kind of violent conflict. It may seem to us like terrorism is random, or “they hate our freedom” or whatever, but for the most part, terrorists are fighting for the same kinds of causes that rebel groups are — and/or they’re exploiting the chaos and power vacuums created by armed conflicts.

My point is this: While counter-terrorism and countering violent extremism are important fields, they shouldn’t take the place of efforts to prevent and end civil wars. In fact, ending civil wars will probably help end terrorism. The need for peacemaking has not gone away.

Great insight and comparison of the impacts of war vs. terrorism. Keep up the good work! Warm regards, Chris